Why Detroit Matters, Part 1: Leveraging Vacant Land as an Asset

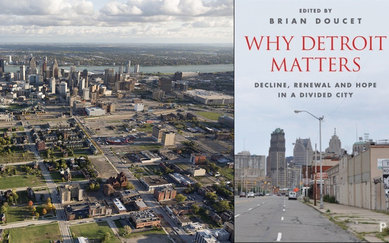

Detroit’s ongoing recovery efforts have led to a wide range of unique and innovative planning and design responses. For the Why Detroit Matters blog series, SmithGroup’s David Lantz sat down with Urban Design Practice Director Dan Kinkead to discuss the chapter Dan wrote for the recently published book Why Detroit Matters: Decline, Renewal and Hope in a Divided City. Dan focuses on Detroit’s emerging and precedent-setting approaches to urban redevelopment and recovery, and their growing significance at a national and international level.

This post introduces the series and focuses on how Detroit is using its vacant land portfolio as an asset for urban renewal.

David Lantz (DL): What’s the story behind Why Detroit Matters? How did the book come to be and how did you get involved with it?

Dan Kinkead (DK): This book was a culmination of several years of focused effort by Brian Doucet, the editor. At the time he was at a university in the Netherlands. He’s a Toronto native, though, and had a lot of interaction with Detroit and has remained connected to the city. Also, as a trained geographer, he was always captivated by Detroit’s story and how it evolved over time.

In many ways this book is a demonstration of his curiosity about the city and what’s happening now amidst the city’s recovery. I was invited to contribute because of the work I had done for the development of the Detroit Future City Strategic Framework Plan, and the establishment of DFC’s Implementation Office.

Brian’s not looking at Detroit not from a top-down perspective, but rather from multi-faceted perspectives that are rendered through a wide array of voices, some of which you might see conventionally in a book like this and others you typically wouldn’t. And so it’s introduced voices that bring the story of Detroit’s recovery to the forefront in a really different way.

DL: In your chapter you focused on the idea of how Detroit’s liabilities have become its assets in recovery, and describe them as “curious advantages.” These include a 60 percent decline in peak population and over 23 square miles of accumulated vacant land.

Explain more about this idea of vacant land as an urban rebuilding block for Detroit. How do you think the use of vacant land there is starting to redefine traditional patterns of property ownership and land use in the city?

DK: I think for many people Detroit’s expansive vacant land portfolio has been both a signal of the city’s challenges and conventional failures, as well as an implicit contributor to its further decline: that somehow vacant land begets more vacant land, and so forth.

Often when people conceive of vacant land in that way, they’re looking through really conventional lenses for performance and success. I think for many others, we’ve tended to look at Detroit, first of all, in a kind of matter-of-fact way to say, “Yes, we understand there are large challenges here, and we do have an expansive vacant land portfolio, but at the end of the day that total land as a percentage of the city’s geography is still slightly less than the total open space portfolio in the city of New York.”

In New York, this land has been developed and maintained as part of a larger open space system of primarily parks. In Detroit this is often residual vacant land. But if we think about the unique ways vacant land can become a real asset and amenity, we begin to view its role and potential differently.

Unlike any other city, Detroit has a unique opportunity to leverage this land portfolio for uses that can ultimately improve health, provide jobs, reduce impacts on the Great Lakes, and supplement our mobility systems. I think over time we’re going to see more and more of this land adaptation taking place in Detroit, and it’ll also help us understand how these unconventional land uses can provide real solutions to many of the problems facing cities today.

For example, looking at it from the stormwater side, Detroit sits at the center of roughly 84 percent of the North American fresh surface water supply, and 22 percent of the globe’s fresh surface water supply. In many cases, when we get a little more than half an inch of rain in less than one hour, it forces our combined sewer overflow (CSO) system to do a direct discharge to the Detroit River and into the Great Lakes.

In past years we’ve averaged around 36 discharges a year, which is approximately seven times the federally mandated limit. There are many other cities across the United States that have similar or worse CSOs, but it just happens that Detroit is in the middle of a mega region that has 55 million people in it, and a $2 trillion annual GDP.

We have to do a better job at managing this key resource, and being at the center, Detroit has the opportunity to use its vacant land to better manage its stormwater and be a steward of the Great Lakes. Not necessarily through conventional greypipe systems, but actually inland through detention and retention and conveyance systems. What’s exciting is since we started writing for the book, we’ve seen some of these benefits come to fruition. The City has enacted new stormwater management efforts to ensure that we start mitigating run-off impacts at a larger, more effective scale.

Once we view vacant land as part of a larger system, in this case a stormwater system, our perception of its value is going to be very different, and a lot more opportunity can emerge.

Detroit’s vacant land has also turned into big opportunities for urban agriculture, bringing a lot of people closer to the land that they’ve lived on for decades. In many ways, this has been a really important part of Detroit’s recovery and its healing process coming through some of the big changes that it’s felt over the last 20 years.

With more people embracing this ability to re-utilize vacant land there are also thoughts of urban reforestry now, of planting trees that can begin to reduce heat-island effect. This could help reduce the numbers of deaths that we have every summer with seniors due to high heat events.

As we see the climate changing over time, and more and more severe weather occurring, we know that land-based systems can be part of a larger resiliency strategy to engage these challenges. If Detroit can use its expansive vacant land portfolio to develop solutions that can guide other cities, that would be fantastic.

Dan Kinkead, AIA, is SmithGroupJJR’s Urban Design National Practice Director and a Principal at the firm.