Clean Energy Lessons from California

“Had the other 49 states reduced fossil fuel use relative to economic activity at the same pace as California starting in 1975, nationwide carbon emissions would have been lower in 2016 by … 24%.”

This research finding from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) intrigued me. What was unique about California’s policies and experience over those four decades that allowed it to combine significant emissions reductions with economic growth?

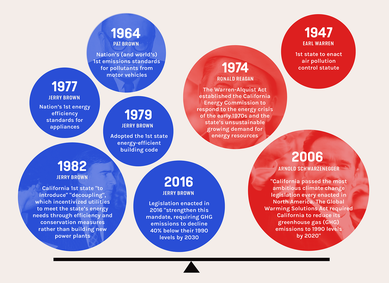

Many people assume California’s current regulations were legislated in a bastion of liberalism. When I began researching this as part of a SmithGroup Exploration Grant, I was surprised to learn many of the most important policies were enacted by conservative as well as liberal governors.

California is progressive, YES. But radical? NO.

These color-coded highlights from David Vogel’s book California Greenin’ show the Republican (red) and Democrat political party affiliations of Governors who signed these regulations into law.

The results achieved in California provide bipartisan evidence for the economic benefits that can be realized by conserving energy and resources while reducing harmful emissions.

Necessity is the Mother of Invention

David Vogel’s book California Greenin’ describes rampant environmental destruction necessitating regulatory intervention. Hydraulic gold mining in the 19th century left farmlands covered in toxic sludge. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw one out of four mature redwoods cut down. By 1972 California’s energy consumption was on pace to require the construction of 130 new power plants by 2002, driving emissions to unprecedented levels.

These potential disasters were mitigated or avoided because of California’s willingness to enact critical and timely public policy. That they were able to do this while growing economically provides a replicable example for the rest of the US. Two regulations stand out as the most impactful: performance standards and decoupling.

Performance Standards

Performance standards set out criteria that must be met in the marketplace and are used in a variety of contexts. In a 2019 interview with Vox, Hal Harvey, founder of Energy Innovation, notes “we use (them) all the time, and they work really well. Our buildings don’t burn down very much; they used to burn down all the time. Our meat’s not poisoned; it used to be poisoned, or you couldn’t tell. And so forth. If you just tell somebody, this is the minimum performance required, guess what? Engineers are really good at meeting it cost-effectively.”

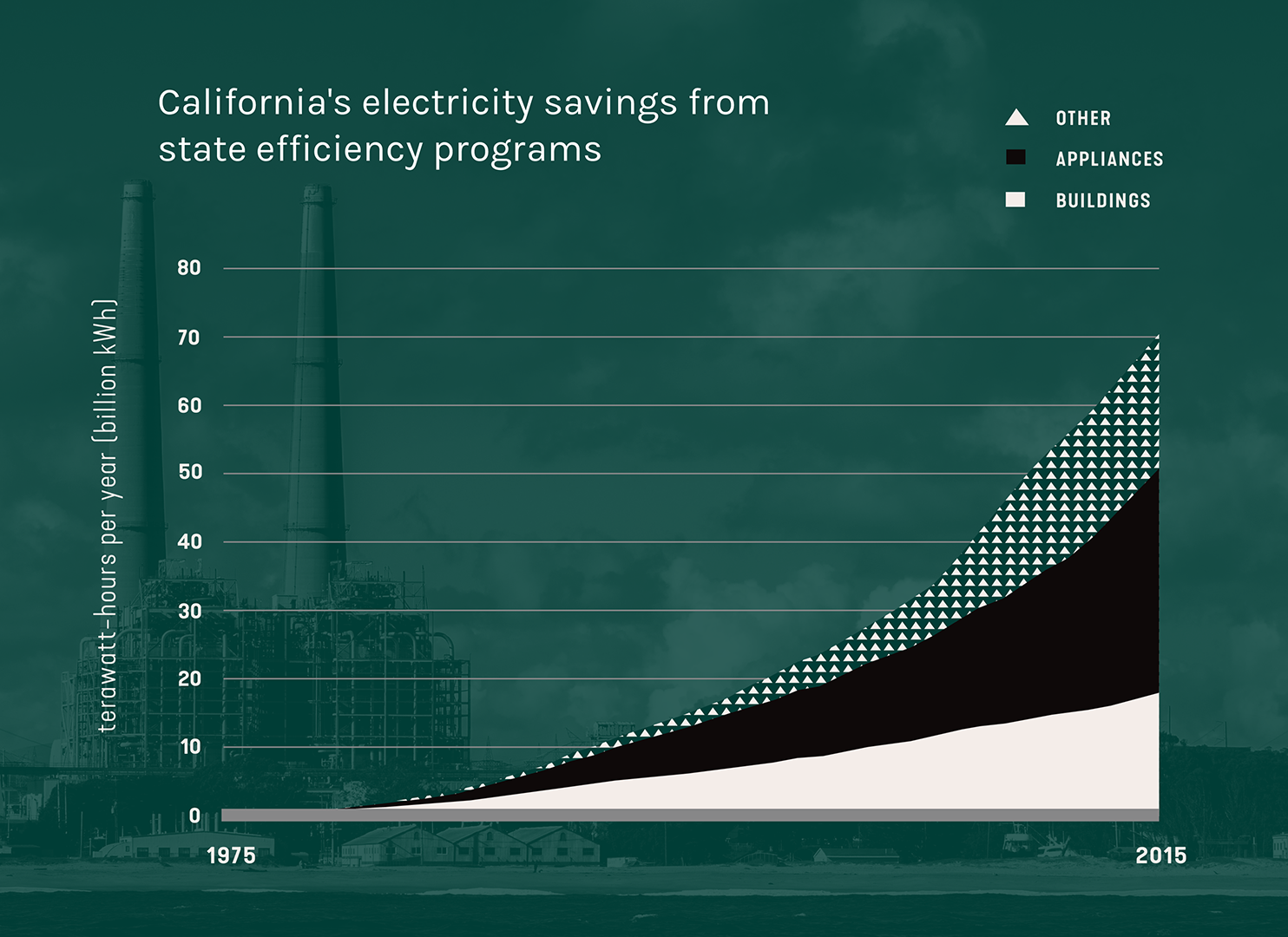

The graph above shows California’s energy savings from 1975 to 2015, highlighting the effectiveness of the state’s appliance and building energy performance standards. Harvey calls attention to what makes these standards successful over the long haul:

“When you design performance standards, there are a few characteristics that make them work really well. The first … is continuous improvement. Don’t set a quantitative target, set a rate of improvement. It’s the gift that keeps on giving. It tells manufacturers you gotta get better and better and better. It helps them structure their R&D. Maybe most importantly, it uses political bandwidth once and delivers the goods forever.”

California’s building and energy codes do just that. They must be updated every three years. This was set in motion with the passage of a single bill: Title 24 in 1978.

Decoupling

California was the first state to introduce decoupling in 1982 as part of an ongoing effort to avoid building more power plants to meet growing consumer demand. Prior to this the financial health of gas and electricity companies was tied directly to sales. Decoupling removed that link.

There are two ways to achieve this:

- Charge consumers a fixed rate for electricity independent of use.

- Make small annual adjustments in rates that wash out fluctuations in sales.

The first approach establishes an all-you-can-eat rate that doesn’t incentivize efficient energy use by consumers. The second is what California adopted. While not a complete solution, it addressed the conflict of interest that had stymied progress on incentivizing efficiency in both the production and use of energy.

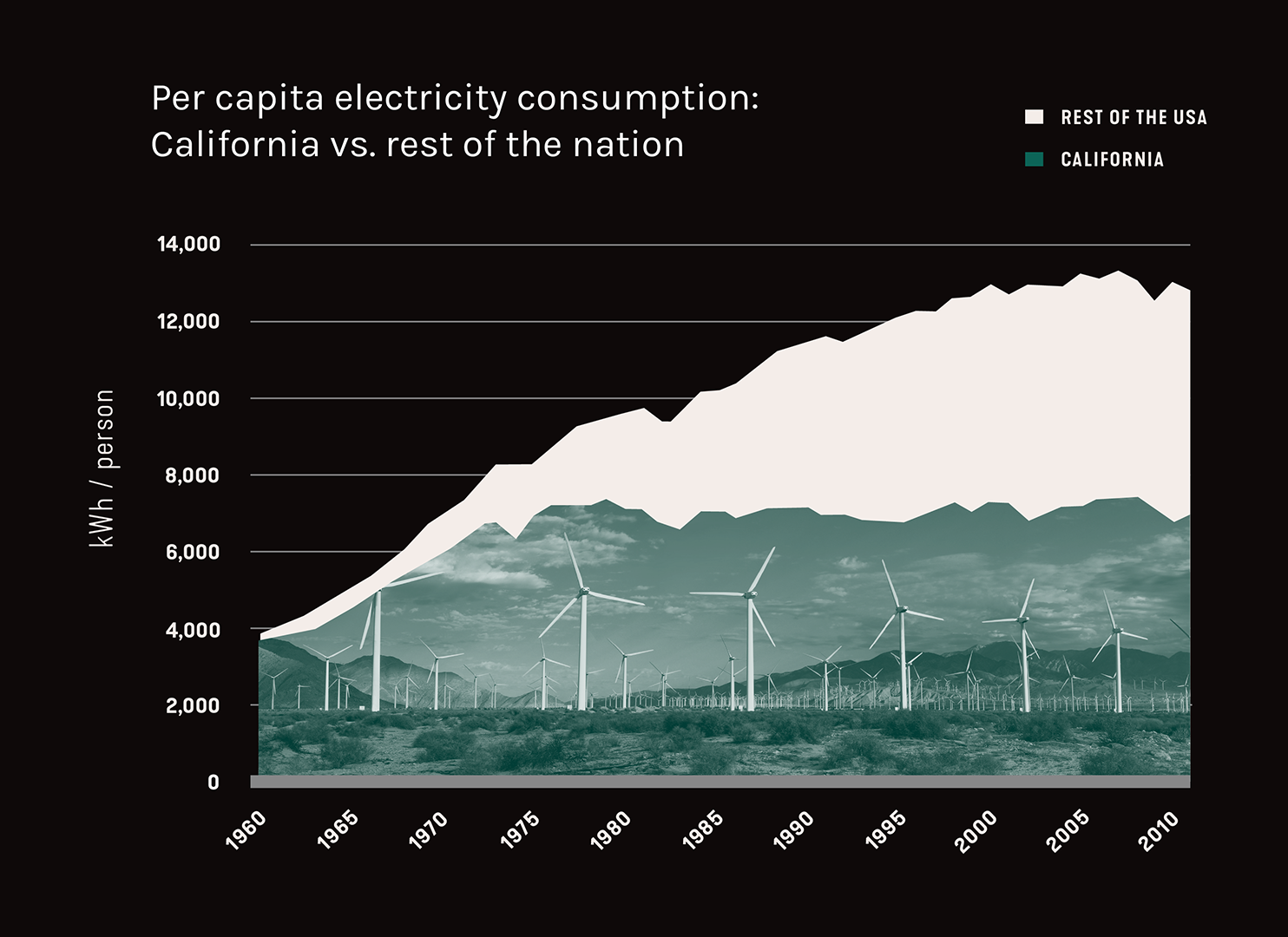

Performance standards and decoupling helped California outpace the rest of the country in its electricity consumption per capita and economically. It also set a much faster pace for emissions reductions in response to climate change.

Setting Standards for Success

How do we extend California's performance benefits in energy conservation, emissions reduction, and economic stimulus to the other 49 states? My research suggests the top five actions are:

- Adopt statewide building codes where none exist currently.

- Adopt a timeframe of three years for state or other jurisdictional building codes to be continually improved, especially where less frequent or no timeframes exist.

- To the extent possible, focus building energy codes on desired outcomes and performance, rather than specific technologies or overly prescriptive design requirements.

- Where decoupling policies have not been adopted, decouple utility companies’ revenues and sales while ensuring their financial health and incentivizing improvements with small annual adjustments in rates.

- In addition to improvements in operational energy standards, push for codes that will help reduce the embodied carbon footprint of new and retrofitted buildings.

It is not surprising that elected officials with limited experience in the design and construction industries struggle to make informed decisions about which clean energy policies to adopt while ensuring the long-term economic health of their communities and constituents. California’s experience demonstrates that continuous improvement of performance standards at regular intervals has successfully protected and advanced both conservative and liberal interests for decades. It is past time to enact legislation that extends California’s emissions reductions and economic benefits to other regions of the U.S.

Curious to learn more about other case studies, your state’s policies, or how to begin advocating for improved performance policies and codes? Robert’s Climate Action Handbook for Design Professionals summarizes his Exploration Grant research and can be read and downloaded here.