Preventative Health for Healthcare Design

Who’s caring for the operational performance health of our hospitals and healthcare facilities?

We focus a lot of our efforts as healthcare designers and planners on developing facilities that help health providers serve the medical needs of their patients. But are we spending enough time understanding the operational performance of these facilities: how their design affects the health of the environment and, in turn, the health of the surrounding community?

The effects of climate-related extreme events, including flooding, wildfires, extreme heat, and poor air quality, are exacerbating cardiac and respiratory conditions and escalating the costs of providing and accessing care. These events are increasing in severity, challenging healthcare providers as they face disruptions in care, manage a surging chronic illness population, and make costly repairs to their facilities.

The operational performance of healthcare facilities directly influences population health. According to the Commonwealth Fund, the healthcare sector is responsible for as much as 4.6 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, with the United States alone contributing 8.5 percent. These carbon emissions cause numerous adverse health impacts, with an increasing number resulting from climate change.

Much of this is a direct consequence of our design choices.

Optimizing Operational Performance is Preventative Health for Hospitals

Resiliency is the ability of a building to withstand or more quickly recover from a threat to its operations. Whether that threat is climate related, a pandemic, or another disastrous incident, hospitals and healthcare facilities have a responsibility to remain operational at all times and continue to serve vulnerable populations.

Just as healthcare providers emphasize preventative health services so patients can live longer, healthier lives, designers and operators of the built environment should advocate for the preventative health of our healthcare facilities. Waiting until after a disastrous event to address facility resilience is akin to having 20/20 hindsight—it reveals vulnerabilities that could have been avoided or mitigated had they been considered from the outset.

We’ve seen time and again that meeting building code minimums does not meet the owner’s and users’ needs for resiliency. So much so that many authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs), such as the Office of Statewide Hospital Planning and Development (OSHPD) in California, are pushing voluntary guidelines and best practices to design beyond code minimums.

New areas of focus in OSHPD’s guidelines include patient room ventilation conversion for infection and contamination control, HVAC considerations for managing smoke from wildfire events, and how to expedite emergency projects through the agency. The guidelines also address how to coordinate with other jurisdictions for temporary surge facilities and alternate care sites.

The healthcare buildings that are most resilient to future threats are the buildings that are as nimble in their design, program, and infrastructure as the care providers and operational personnel who work in them. Any health organization can take foundational steps to improve the resilience of its buildings and infrastructure, whether renovating or constructing new. Greg Heppner outlined these in the first part of this two-part look at healthcare resiliency.

While intensifying climate-related disasters are pushing healthcare systems to address resiliency, the need to address the health systems’ contributions to climate change is also becoming more apparent and urgent.

Monitoring Facility Vital Signs for Sustainability and Decarbonization

Recognizing the need to address both the causes and effects of climate change, The Joint Commission, which accredits nearly 15,000 healthcare organizations across the United States, announced a voluntary Sustainable Healthcare Certification (SHC) program. The SHC program is intended to accelerate the efforts of healthcare organizations in implementing a Climate Action Plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and advance other sustainability efforts.

As outlined in the SHC, the first step is to measure and monitor the operational performance of your facilities. These can be viewed as your building’s vital signs, and include energy consumption and production as well as carbon and greenhouse gas emissions. Understanding these vital signs allows you to make a plan toward carbon neutrality or positivity.

Resiliency often connotes redundancy and robustness, which on the surface can seem in opposition to building less to reduce carbon emissions and maximize efficiency. SmithGroup’s Stet Sanborn, co-leader of IMPACT (the firm’s national Integrated Multidisciplinary Performance Analytics Climate Team), believes this doesn’t have to be the case.

"If the design is done right, resiliency and sustainability can support each other in meeting their goals," says Sanborn. "A great example is the microgrid analysis we completed for a new net-zero energy healthcare administration building for a Central Valley provider."

Adapting microgrids into the healthcare realm makes perfect sustainable, resilient and business sense, especially as healthcare providers face instability in future energy costs and pressure around ESG reporting.

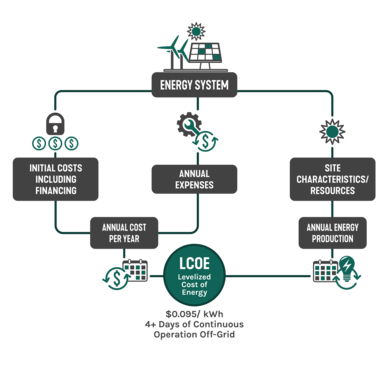

After a careful analysis of electrical load profiles and evaluating risk parameters like preemptive power shutoffs due to wildfires, SmithGroup’s design team developed an in-depth techno-economic model for an all-electric administration building that fuses decarbonization with enhanced resilience.

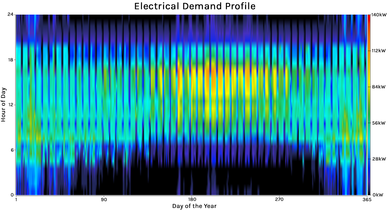

The Hourly Electrical Demand Profile below provides a 365-day understanding of the diurnal (day to night) and seasonal variations in electrical demand for the proposed net-zero healthcare administration building. Demand profiles inform the sizing of on-site solar panel arrays and battery storage to meet electrical needs during power outages while reducing operational carbon emissions.

Variations in energy demand due to building use, occupancy schedules, and time of year are visualized as variations in color. The yellow and orange areas indicate increased electrical demand during summer daytime hours due to air-conditioning, while the darker vertical bands indicate weekend periods of reduced use.

The client selected a design option that achieves net-positive energy, locks in a long-term, stable levelized cost of energy (LCOE) below $0.10/kWh, and provides more than four full days of back-up energy if the grid goes down. All of this was accounted for while achieving a 4 percent internal rate of return on the project. By providing full operational resilience as well as a hedge against future energy-cost volatility, the design helps ensure sustained healthcare benefits for the client and the community.

An Ethical Obligation to Do No Harm

The Hippocratic Oath serves as a vital reminder for health practitioners of the ethical responsibilities of their work. It emphasizes the commitment to uphold human life, dignity, and health. As designers of the facilities that support that mission, we can help uphold the obligation to do no harm by addressing how our design decisions can reduce adverse health impacts on the building’s users, the environment, and the surrounding community by reducing a facility's carbon footprint.

We know that climate change increases particulate matter levels and ground-level ozone, reducing air quality. We also know it leads to earlier and longer pollen seasons with higher pollen potency. Increased precipitation events promote mold growth. All these impacts exacerbate asthma and allergies and adversely affect lung and heart health.

An increasing number of studies, like the EPA’s Social Vulnerability Report, indicate that communities of color are disproportionately exposed to the adverse health impacts caused by climate change and are at a greater risk of being hospitalized and dying from the effects of more extreme temperatures, storms and decreased air quality. This will increase the existing racial and ethnic disparities in U.S. healthcare access and outcomes seen in all 50 states.

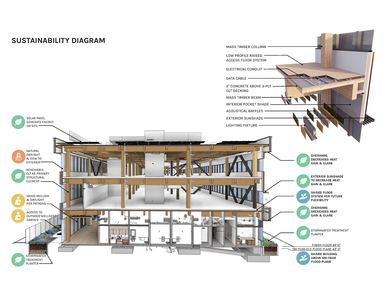

San Mateo County’s Wellness Center extends healthcare services to a previously underserved area of the county – with a high-performance design featuring healthy and low-carbon materials, all-electric operations with on-site renewable energy generation, and the ability to serve as a refuge for the community during emergencies.

It is essential to view resilience and decarbonization as fully integrated parts of healthcare’s model and mission—and to recognize that business as usual must change to fulfill that mission. The National Academy of Medicine has recognized this, aiming to serve as a nationwide coordinating body for health organizations by creating the Initiative to Accelerate the National Climate and Health Movement. Organizations and health systems that sign up for the initiative have opportunities to forge collaborations, receive updates about the most impactful climate work, and track collective progress.

It’s no longer enough for our healthcare facilities to heal; they must also strive to do no harm through their construction and operations. By monitoring and caring for the overall performance and health of our healthcare facilities, as much as we do for the patients inside them, we can improve the health and well-being of every life affected by that facility—inside and out.

Check out the first part of this two-part series on healthcare resiliency, exploring how healthcare providers can more effectively plan and prepare for the growing impacts of climate change.