Inclusive Design & Social Resilience

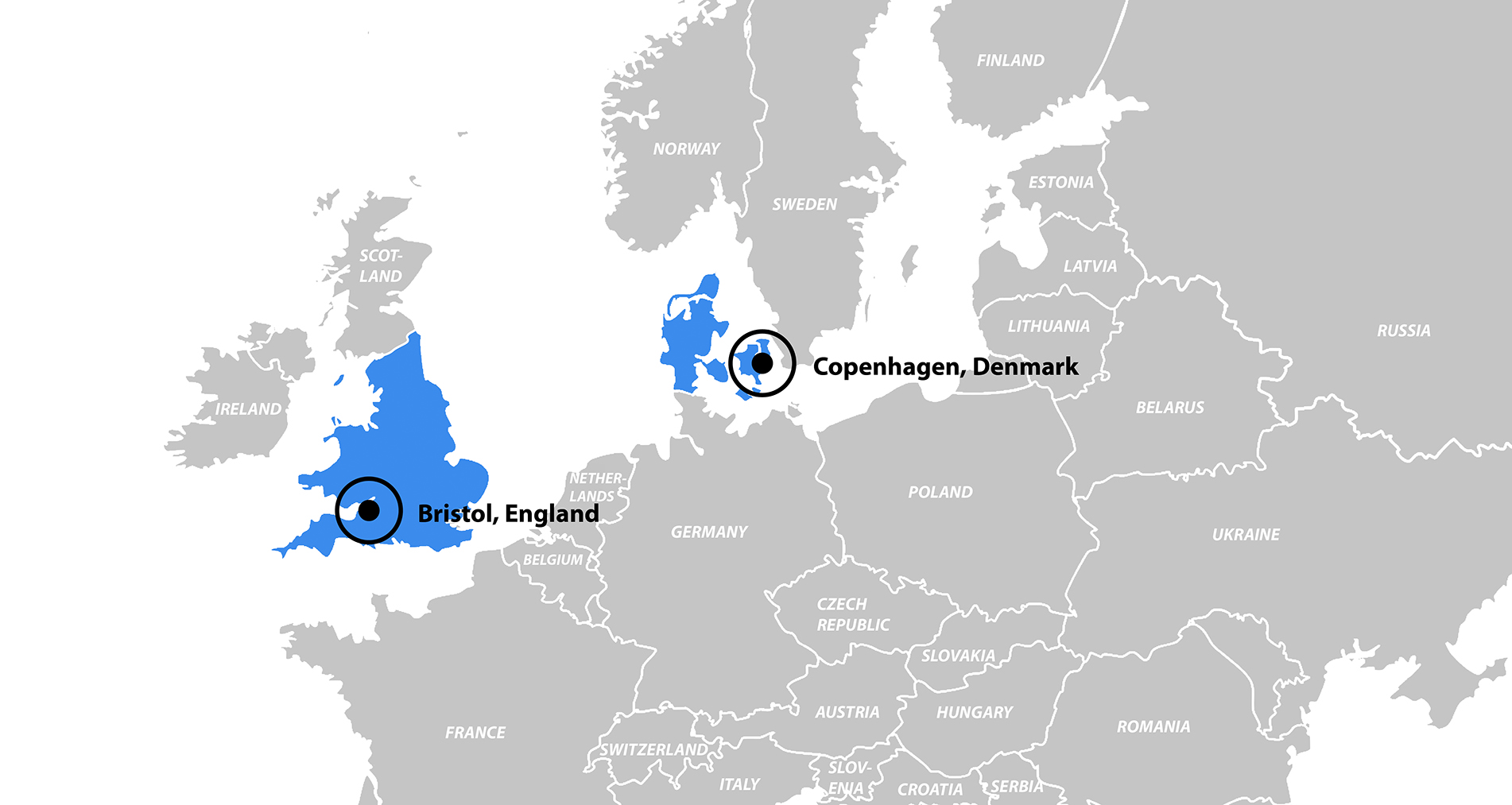

Last year I spent five months working remotely from Copenhagen, Denmark and Bristol, England, spending every spare moment soaking in the impact of urban planning and design on the lived experience. While there, I researched inclusive design strategies by conducting a literature review and three case studies: two in the Nørrebro neighborhood of Copenhagen, and the third in the Stokes Croft area of Bristol. This post is the first of a series summarizing my research.

Social resilience is critical to the increasing number of cities setting resilience goals, as it directly impacts the ability of cities to adapt to acute shocks and chronic stresses. People are the ones who change their built environment through small and large interventions alike. It’s the bond between people – the strength of the community – that fosters movements to improve urban environments for the better. Not only do people shape their environment, but the reverse is also true; that environment contributes to the strength of the community. However, when it comes to urban improvements crafted by design professionals, social issues are often overlooked in favor of more easily quantifiable urban systems. Designers and planners have the obligation to address social issues and take a more holistic approach to resilience in order to help communities better prepare for an uncertain future.

One way designers can increase social resilience is through inclusive design. Research demonstrates that three critical facets of social resilience can be improved through inclusive design: social cohesion, social equity, and mental and physical health. Cities all over the world have identified these three facets as key areas for improvement to increase their resilience (100 Resilient Cities).

Social cohesion can be increased through interactions between different groups within a community (Cutter, 2010). For these interactions to happen in public open spaces, multiple groups of people must use the spaces. Inclusive design promotes the use of spaces by all groups within a community, thus fostering social cohesion by facilitating chance interactions between different cultural groups.

Social equity and the mental and physical health of a population are negatively impacted by a lack of access to quality open space. Current research finds that access to parks is a social determinant of health. In other words, neighborhood parks improve a community's mental and physical health (Jennings et al, 2016). While merely living near a park provides some benefits (such as improved air quality), those who use the park receive the most benefit (Bedimo-Rung, 2005). Inclusive parks improve equity and mental and physical health by welcoming all people.

Including the Often Excluded

Public spaces often exclude people due to their race, gender and/or economic status because they perceive a space as unsafe or "belonging” to another group in the community (Brownlow 2006) (Byrne, 2012). Additionally, it is common practice in urban design to exclude certain "nuisance users" - skateboarders, homeless populations, refugees, members of gangs - by making spaces inhospitable to their needs. To create inclusive cities, this practice needs to change. Public space can serve more people by welcoming marginalized groups to use those spaces as equal members of the community.

In concert with a shift away from exclusionary design, the rhetoric frequently used to describe marginalized groups needs rethinking. Expelling derogatory and dehumanizing language from design discussions and instead using equitable and inclusive wording is a first step towards inclusive thinking.

Studies of Inclusive Open Spaces

To evaluate strategies for creating inclusive spaces, I assessed three case studies: two in Copenhagen and one in Bristol. These spaces were chosen due to their intentional inclusivity and location in neighborhoods experiencing social tensions between diverse groups of people. The case studies from Copenhagen include Superkilen Park and Folkets Park and the case study in Bristol is The Bear Pitt.

The next post in this series will review these case studies and discuss my initial findings. See my research report for more information on inclusive design and see my travel blog for reflections on my experience visiting these areas: Nørrebro and Stokes Croft.

Works Cited

"Selected Cities." 100 Resilient Cities. 2018. Accessed September 18, 2018. https://www.100resilientcities.org/cities/