From Worn to Reborn: Reimagining Aging Classroom Buildings

With pressure to deliver better performance and outcomes, coupled with cultural and campus ambitions to resist the erasure of legacy, you may ask: What can be done with a fifty-year-old classroom building? It may look outdated, but beneath the wear and tear lies real potential to transform it into a modern teaching and learning asset. Here are three design questions to explore when trying to reimagine how aging classroom buildings can be reanimated and become a valuable part of your campus future.

Is it Time to Rethink Your Façade?

Nothing quite places a building in its era like its exterior skin. Is it the ugliest building on the historic quad, or the one with the fewest windows? Perhaps, but this is the time to move past first impressions, study its inherent opportunities and shortcomings and address building performance and adapt to climate imperatives. There is no one-size-fits-all solution.

The building envelope works in tandem with its systems, and in many aging structures, both require major upgrades. Many older wall assemblies are difficult to modify and suffer from poor air or thermal performance, minimal insulation, and outdated glazing. Fortunately, modern tools such as infrared thermography, laser scanning, and hygrothermal analysis allow for a comprehensive evaluation of the envelope and systems simultaneously.

With this data, you can make targeted, cost-effective improvements, whether by adding insulation to the interior or over-cladding, replacing windows, reskinning the exterior, or using a combination of these strategies. The human impact of these changes should not be overlooked. Does it lack presence on campus because it is opaque, or does it inhibit student activity along major outdoor spaces? Is it an aesthetic that seems dated or simply one that has no dialogue with the buildings around it? Or perhaps it’s a style that today’s students might perceive as having negative cultural significance? Is it the wrong scale, rendering important parts of campus unusable? Many of these questions can be addressed with the same strategic interventions that enhance the envelope’s performance.

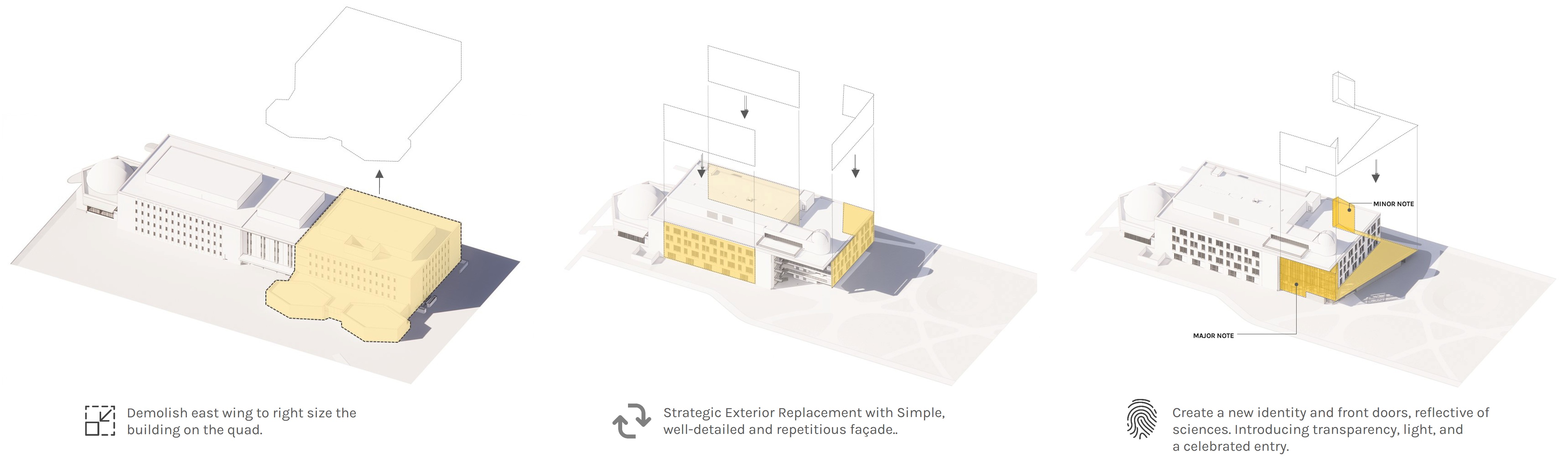

Constructed in 1967, Ball State University’s Cooper Science Building featured a façade that offered little transparency to the campus community, with narrow vertical windows. The 300,000 gsf facility was large and felt out of context alongside its historic neighbors.

The slimmed-down result introduces a student-focused hub right on the historic quad. The updated exterior is sensitive to the surrounding historic context without duplicating it. Updated MEP systems enable connections to the campus geothermal grid, positioning the building well for the next 50 years.

Is Your Classroom Interior Helping Students Thrive?

The demands to prove efficacy and justify the costs of higher education are echoed by the same demands on construction costs, especially challenging amid volatile cost escalation. It is typically less expensive to renovate than to build new, to leverage existing structures and foundations, and to creatively or strategically modernize the envelope. We cannot forget why we are considering updating the building in the first place. An interior environment with “good bones” should support modern teaching and learning, foster a sense of belonging, and offer a connected network of spaces, from classrooms to group study areas, focus zones, and vibrant zones for student engagement and visibility.

Floor-to-floor heights and column spacing are key considerations, of course. Whether learning environments can achieve the flexible space and sightlines required by specific pedagogies is fundamental. Often overlooked in these numerical conversations is the hidden value resulting from the context of that mid-century-ish mindset— the modernist beautiful machine — that though characterized by its own issues, often ends up offering significant opportunity.

Obsolete service corridors and oversized shafts can be repurposed into study spaces or used to create accessible routes to previously inaccessible tiered classrooms. Generously wide corridors with unused lockers can be transformed into student spaces that enlivens those corridors and provides visibility and borrowed light to the core while creating character.

In a world where experience is at risk of slick homogeneity, where costs potentially drive toward off-the-shelf solutions, the patina of an aged building may hold an almost irreplaceable character that can contribute to a particular sense of identity evoked by this place alone that students seek. The beauty of rough, exposed concrete beside warm and welcoming materials; that peculiar, vaulted ceiling of which no one recalls the origin; the scrubbed residue of old adhesive on a wall that looks like a delicate Paul Klee canvas. They are at once a critique of an ephemeral Instagram culture and are of course imminently Instagrammable.

At Wayne State University, Wilson State Hall’s existing conditions included generously wide corridors originally designed for lockers. By taking advantage of valuable circulation real estate, the footprint of the former lockers was repurposed as pre- and post-classroom space, including power benches and bars, nooks, and study booths that create a destination as valuable as the classrooms themselves.

Can You Optimize Classroom Utilization and Renovate Efficiently?

How can you possibly shut down a heavily scheduled building to update it? Swing space is typically scarce. Phasing is possible, but an extended timeframe inevitably leads to higher construction costs.

This is a good time to compare predicted classroom use with actual classroom utilization, studying not just how much classrooms are used, but how well. Campus-wide analyses of weekly room hours, seat fill rates, and square feet per student provide a clear-eyed snapshot of your processes and may also help make the renovation of your main classroom building more feasible.

The University of Kentucky is currently renovating White Hall, a late-1960s classroom building that housed about 30% of all the classrooms in the academic core. Shutting it down for renovation once seemed unthinkable, especially amid a perceived need for even more classroom space.

A campus-wide study revealed that utilization was lower than previously understood. Certain types of classrooms were overburdened due to their location or technology, and some scheduling was inefficiently decentralized. With small scheduling modifications that increased existing classroom utilization, White Hall was able to be shut down and renovated all at once, resulting in considerable savings compared to a phased construction process.

Closing Thoughts

There will come a time when we are able to talk more concretely about regenerative design on campuses, about buildings that perhaps don’t decay, or that are intentionally transient, designed as part of a more cyclical system.

And there will be times when the reinvestment just doesn’t pay off; perhaps the original building is too idiosyncratic, too fixed in its time. We must do what we can to resist the urge to discard and take every opportunity to realize the full potential of what we already have in-hand.