Racial Equity in Urban Redevelopment - Part 1

An interview with Anika Goss-Foster, Executive Director, Detroit Future City

Over the last several months the combined impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and long-standing structural racism have driven a conscious and existential awakening regarding race, public health, policy and perception. Not since the foment of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s has such a powerful clarion call been raised for racial justice. Many are asking how to best transform the grave challenges we face into a new consciousness that fosters equity in how we build and rebuild our cities.

It’s within this context that many in the design and development industry are grappling with their own unconscious biases in methods, strategies and outcomes. While often seen as a result of existing policies and clients’ economic interests, development ultimately yields strategic and built outcomes that impact lives. Now more than ever, we must assert greater awareness and intentionality around the social and racial impacts of our urban design and development work, while recognizing the failures of our past and our responsibility for a consciously inclusive future.

Dan Kinkead, SmithGroup's Co-Director of Urban Design, recently had the opportunity to talk with Anika Goss-Foster, the Executive Director of Detroit Future City – a non-profit organization dedicated to improving quality of life for all Detroiters. The two spoke about her experiences working in community development for the majority of her career, and her perception of design and development in cities, especially her native Detroit. What unfolded was a robust conversation that examined not only how we arrived at where we are today, but how design and development practices can – and must – be more directly driven toward an inclusive and equitable future. We share their conversation with you in a two-part series of posts.

DK: Looking back over your career in community development and urban advocacy, you’ve covered significant ground including an underlying commitment to racial equity and justice. This goes back to your time with LISC (Local Initiative Support Corporation), your work with the City of Detroit, Detroit Future City and beyond. Could you describe what that work has entailed, and within the context of where we are today, what motivates you?

AGF: I feel like I’ve been working in the field of community development since I graduated from school. Other people find their way into this realm over time. For whatever reason, I picked the hardest area of work from the onset.

I’m a social worker by training– which is really interesting now in these complicated times. There is a difference between psychology and social work. Psychology looks at an individual’s problem that needs to be resolved. With social work, you work to get to know an individual and understand how they are impacted by the system and environment around them – which could be a family system, the community that they live in, or a combination.

I’ve taken that theory, turned it on its head and created a career out of community development.

When you’re 22 years old, you never really imagine that your first job could actually lead you to your life’s work. But in my case, it all fit. So my purpose has always been focused on how we create agency in neighborhoods, particularly neighborhoods where African Americans and Latinos live and are concentrated in poverty and lack resources. My work has focused on, “How can we connect people to resources that allow and enable them to make changes for themselves?”

I never wanted to work as a traditional social worker, where the model is that you are constantly giving something. I suppose much of this perspective comes from my own personal family story and the realization that wherever a person may be living, if you don’t have options, opportunities, choices this will create barriers for you. When this is the case, you, your children and your grandchildren are never able to move past them.

I’ve been lucky enough to have jobs that enable me to have a positive impact and make change.

It’s funny. I’m a social worker and I can’t believe that they keep letting me around the money. (laughs)

There’s a lot of power in being able to say we can use this capital to create change and community. And that’s really why I was at LISC for so long.

DK: Let’s expand a bit upon your background and motivators, and your recognition that more needs to be done for individuals who suffer from isolation and inequity. For you, are there experiences or watershed moments that reinforced the importance of your work?

AGF: I’ve thought a lot about that. What is it about this particular moment that would be on a parallel plane to other moments in history? What I really believe is that we have come to a point, as we have so often throughout the history of the United States, that represents a boiling point. And when I say boiling point, I don’t mean just the events that took place in Detroit in the summer of 1967, which is often equated to what we are seeing today. Instead, I’m actually referring to a pot that is boiling. And feelings of oppression and frustration that date back as far as the founding of our country, when the United State was still under Britain’s rule. Our founders had dreams and goals that they were striving for and working towards, but they could only get so far. Taxation without representation, unlawful land grabbing, lawlessness – these were all taking place at once, making people felt incredibly oppressed, keeping them from achieving their own dreams and success.

My family dates back to colonial Virginia. My ancestry is Black on my mother’s side. When you read about people’s experiences during that period there is documentation of unrest and disputes, Stories of discord and fighting and threats of death over theft of livestock. It was a way of life.

So we have to keep that in mind and then fast forward to reflect on how much our entire nation changed between slavery, the Civil War and Reconstruction. The level of oppression was unimaginable, and as a result, the United States came to another boiling point. And at that time, so much of the strife focused on livelihood and oppression and what people believed were fundamental American values.

Later in our history we move into the Civil Rights movement. Again, the focus remains on fundamental rights that so many people – Blacks, Native Americans, Hispanics, Asians – did not have. At that time, the majority of those leading the charge were African Americans. But prior to the 14th and 15th Amendments during Reconstruction no one was able to vote unless you were white -- a white landowner, a white educated person. With a deference to state laws and Jim Crow laws, challenges to African America voting rights remained robust. And so there had to be a hard shift at that time in our history as well.

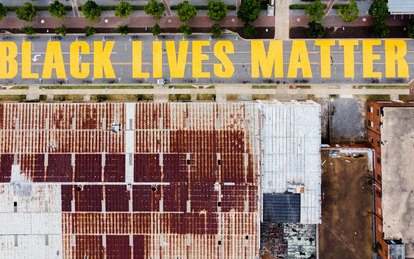

Which brings us to where we are today. In the middle of a pandemic. Millions of people are out of work. George Floyd is killed. There is renewed focus on the Black Lives Matter movement, which is not new and has been building for several years. And conversations around police brutality are back in the spotlight.

As an aside, this is an issue that has been prevalent since slavery and Reconstruction. Police were originally slave catchers. The modern-day institution of policing grew out of that model, which began as a military unit, of sorts.

But now, we are at a point where people are sick and dying due to the COVID-19 pandemic – to date we’ve lost over 1,600 people in Detroit, and nearly 180,000 across the country. And we see people continuing to lose jobs, or lose businesses that have been in their families for generations. And we see people getting pulled over without cause. And then you go home, turn on your television and watch as George Floyd dies at the hands of police officers. So, now the oppression that people have been feeling for so long has become very personal for so many.

People have had enough. It’s time for that boiling point again. Why does it happen? What triggers it at a certain point in time? We don’t know.

But we do know that now we are at a crossroads. We have allowed communities to remain so poor for so long, where they have been held hostage by their own neighborhoods – where there is zero opportunity. You can live for generations on public assistance, never able to get out of your neighborhood.

What we are learning at this moment in time is that it is finally okay to say out loud that some of this is by design. That systems were designed by those in power to target African Americans and Latinos, keep them down and make it as difficult as possible for them to get anything more than what’s in their neighborhood or low-income housing development.

COVID-19 IMPACT

DK: You make so many great points. When I think about this from my perspective of white privilege, you recognize that some people – perhaps for the first time – are beginning to understand a collective blindness to the realities you’ve just described. Of course, there are individuals who want to do good, to make things better. But the irony is that they are operating within foundational systems that have evolved from centuries old models of urban segregation that were, in fact, created to oppress: And now, in the face of COVID-19, it’s undeniable that the concentrating of people in certain conditions over long periods, with limited access to healthcare, makes them even more vulnerable and compounds the problems they’re facing.

AGF: I think people don’t even realize how compounding the problems were until COVID-19 happened. In fact, when you shine a light on all of the issues, the pandemic brought so much of this to the surface.

For instance, here in Detroit we only have three major hospitals. So, if you get ill, you have three places where you can go for treatment. But what if you’re really sick and all those places are filled up? And you don’t have money or access to transportation to go someplace else? There were so many things that were keeping people from getting the support they needed when they were sick. Families were dying. It was heartbreaking to hear stories. A colleague I’ve worked with lost 19 family members, including her father, to COVID. This isn’t somebody random. It was a professional, a person we know who had resources and options.

RACIAL + SOCIAL INJUSTICE AND DESIGN

DK: The long-term and systemic impact of these inequities and lack of access has been downplayed for so long. Unfortunately, it takes something like this to reveal how fragile and interconnected everything is. I recognize that broad segments of society feel that significant strides have been made in recent years towards ending racial and social injustice. But what we are experiencing in this moment suggests that there is still much more to be done. From your perspective what could the design and development industries do to keep momentum going? And perhaps more importantly, how do we measure success?

AGF: When it comes to designing neighborhoods or living accommodations for people of color, one big challenge I see – which is both a design issue and urban planning issue – stems from the fact that many assume that the standard for how people should live is based upon white standards. This in and of itself is problematic. From a design standpoint, we really need to consider the communities and their needs. Within the African American community there are typically more multi-generational and single-parent households than in any other community. We also see more cases where there are males living with the family who may not be a permanent father figure. Additionally, there are many instances where children within a broad span of ages are living within one household, and those children may not all be the children of the head of the household.

This is critically important because often designers believe that neighborhoods should be modeled after traditionally white, suburban neighborhoods – big houses with lots of windows and a garage in the front organized around grids of streets. Or they think they should resemble townhouses, where homes are all adjacent to and organized next to one another. Another common misconception has to do with affordability. Often, designers and developers equate the term affordability with two-bedroom units. As a result, we have lots of two-bedroom units being built across the city. But what these designers and developers fail to realize is that two-bedroom units do not adequately accommodate the needs of larger, multi-generational, multi-family residents.

For the first time, this moment of disruption has allowed us to talk about these kinds of issues. Up until this point we’ve never been okay talking about it. And equally disconcerting, we know that there have been planners and architects of color that are in the room when these kinds of projects are being developed and they haven’t been willing or able to voice opinions like, “Hey, wait a minute. Data tells us that in this zip code there are more families and more seniors raising their grandchildren than anyplace else in the city. How will they live in a two-bedroom house or apartment like this?” So in the end, they do whatever their client or the developer wants.

DK: The points you are making really hit home for me. A few years ago while working on a redevelopment strategy in a near eastside neighborhood of Detroit, our engagement process revealed tremendous depths and impacts of poverty within the community. There was a very high rental profile in the area, indicating that people aren’t able to build durable, long-term wealth or come up with the capital required for a down payment on a property. In addition, family sizes and ages of those within a household were incredibly wide ranging. We explored the possibility of creating a cooperative housing system of sorts, which would enable people to remain within a community but move through different housing types as their needs or situations changed. We thought this could be a positive departure from the somewhat terminal way that people often think about housing – you go into a house and you live in the house for the rest of your life, regardless of your needs or resources.

AGF: I This is something that we’ve talked about for years. However, the reality is that most people or industries don’t like to think about changing how they work, and the most influential institutions within these systems – enterprises like banks and financial institutions – are the most difficult to change. Which means there’s a great deal of bias that we have to unpack. Conversations like, “If we create something beautiful for people who’ve never experienced anything beautiful how will they react? Will they tear it up and it’ll look terrible?” Or “If we build them something and give them all of this access will they even know what to do with it?” These are just a few examples of real-life bias that exist within different institutions.

The impact of grid streets is another important thing I learned while working with the City, particularly if you have the opportunity to replat. Take the Detroit communities of Palmer Woods and Sherwood Forest as examples. They city replatted these areas and closed some of the streets, which is a tremendously successful crime deterrent and a community builder. But these areas have the resources to say to the City “This is what we want, and this is how we want it to look.” Unfortunately we don’t often think about things like this in poorer, urban neighborhoods who don’t have the same resources or voices. And the city doesn’t want to make the investment in these areas.

DK: This conversation brings to mind a set of standards known as CPTED - Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design. Not so long ago, these standards were considered the gold standard when it came to creating environments that would deter criminal activity because they provided for open, accessible sight lines which would both enable people to see what’s happening while helping those who might otherwise feel vulnerable to feel safer and more secure.

The most recent happenings, include a robust critique regarding implicit power dynamics in design spurred by Black Lives Matter, have us taking a new look at how we design and build places and to address much of what you’re speaking to. They are giving rise to a new awareness regarding how certain standards and systems disproportionally scrutinize and set up minority populations, particularly African Americans, for isolation.

For many of us in the design community, this conversation has turned things on their head. And if we were to discuss possibilities like these more openly in community engagement meetings, residents would advocate for some of the solutions and changes that we’ve discussed. But, as you mentioned, it is becoming more and more clear that biases are implicitly built into the power dynamic that guides those decisions. So often, many in the design community feel good about certain changes that we are helping to advance, while unwittingly creating solutions that actually reinforce what we claimed to be working against. And that can be hard to wrap your head around. We all must be open to critique and be prepared to help making the changes that are necessary to move beyond where we are presently.

AGF: Now is definitely the moment to put everything on the table.