Why Detroit Matters, Part 2: Connecting Green Infrastructure and Neighborhood Revitalization

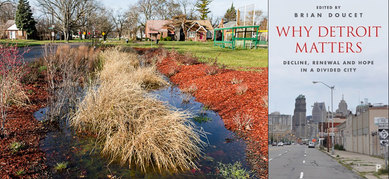

Detroit’s ongoing recovery efforts have led to a wide range of unique and innovative planning and design responses. For the Why Detroit Matters blog series, SmithGroupJJR’s David Lantz sat down with Urban Design Practice Director Dan Kinkead to discuss the chapter Dan wrote for the recently published book Why Detroit Matters: Decline, Renewal and Hope in a Divided City. Dan focuses on Detroit’s emerging and precedent-setting approaches to urban redevelopment and recovery, and their growing significance at a national and international level.

This post looks at the connection being forged between green infrastructure development and revitalization in Detroit’s neighborhoods.

DL: You wrote about a couple of compelling pilot project initiatives in your section about blue and green infrastructure in Detroit. There’s the Upper Rouge Tunnel Green Infrastructure Initiative in the Brightmoor neighborhood. How is that progressing?

DK: That was one of the earliest publicly driven efforts to consider alternative approaches to managing stormwater in the city. In Brightmoor, you have the City and a key consultant, in this case Tetra Tech, leading an effort to test a series of pilot strategies and how they might work to supplement the fixed stormwater infrastructure system, the gray system. In this case they’re taking advantage of one of the few areas in the city that has natural topography, and it’s pointing to methods that may also work in other parts of the city.

It’s also a mark of vision for many public entities to look beyond costly large underground concrete storage systems, recognizing such systems are unable to manage long-term systemic challenges that we see emerging. We do have to think about more of an adapted solution that can happen on the ground that’s less capital intensive and more flexible.

DL: What do you see happening in the Near Eastside Drainage District? There seem to be some interesting partnerships there that go beyond the green infrastructure piece to get into larger neighborhood-building efforts.

DK: I think with the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funding that was drawn down in 2014 and 2015, a broad public-private partnership emerged between the City, consultants, nonprofits and philanthropy, and the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments (SEMCOG), the regional planning body in and around Detroit, to see how key parts of the city’s lower east side could be reconceptualized with the idea of actually managing stormwater in place. This engaged key nonprofits such as RecoveryPark, whose mission is to provide employment to folks who have high barriers to employment due to incarceration or drug use. They were trying to find new features for people, and in their effort to create a large-scale urban agricultural enterprise on the city’s east side they have incorporated substantial natural stormwater management systems.

East Side Community Network is also doing that, and deploying it at the community level and considering how these strategies can be integrated into neighborhoods and along corridors. This includes former commercial corridors like Mack Avenue, and testing those strategies over time.

L: The contiguous scale of Recovery Park Farms seems unique, as far as urban agricultural efforts are concerned. The city’s invested about $15 million into it to move the initial 5-year phase forward, but we’re talking about 60 acres that are dedicated to ag. within the city, right?

DK: It’s a significant scale. In other cities where urban ag is growing, like Chicago, we’re seeing more vertical farming development, with smaller growing sites spread out over a larger geographic area. But the ability to aggregate land for new uses in Detroit allows for a different approach.

DL: I’m intrigued by this combination of commercial agricultural development that employs people who are recovering from addiction or have other barriers to employment, and that also integrates natural stormwater management at a large scale. It’s just a powerful blend of responses.

DK: The model Recovery Park is deploying is certainly uniquely developed to engage the many challenges that Detroit is facing. This includes access to fresh produce for many Detroiters, but it also includes strategies for reutilization of vacant land, putting it into productive use, helping to clean it up over time, to support stormwater management, and then provide key workforce training that can actually provide long term benefit to folks who’ve had real challenges in the past. I think it’s a pretty compelling, comprehensive strategy for the city and its residents.

Dan Kinkead, AIA, is SmithGroupJJR’s Urban Design National Practice Director and a Principal at the firm.