Campus Landscape Planning of the Future: A University of Wisconsin-Madison Case Study

During my undergraduate years at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, I’ll admit that I was more preoccupied with my exams and post-graduation plans than with the campus’ landscapes and stormwater management techniques. Fast-forward nearly 10 years, and I find myself deeply humbled after helping lead the campus master plan update at my alma mater alongside a talented, multidisciplinary team. I’ve been able to witness how this opportunity has evolved into a national green infrastructure precedent that challenges traditional landscape master planning methods.

The team, comprised of nearly all UW-Madison alum, had a lot to work with—a 936-acre campus occupying an intersection between the capital city’s urban vitality and Lake Mendota’s natural beauty. While universities typically develop separate landscape and stormwater management plans, UW-Madison sought to create one of the first joint plans, fully integrated with the larger campus master planning efforts. This approach framed the “Big Question” of the project: How do we create an integrated landscape framework that preserves the university’s historic core, elevates the quality and identity of the overall campus, better connects the entire community to Lake Mendota, and establishes rigorous, measurable standards for improved environmental stewardship?

There are many factors to consider, but the answer lies in the unique, comprehensive integration of a more traditional campus landscape planning process with a high performance-based green infrastructure approach. Recognizing that the future health of the campus and lake are interdependent, this innovative approach will achieve significant improvements in stormwater management and water quality within the university’s restored, more connected network of historic and culturally rich landscapes.

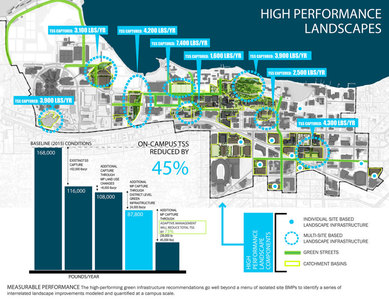

Creating a Performance-Based Landscape Framework

Our landscape master planning approach goes well beyond recommending a menu of typical isolated green infrastructure and stormwater practices, to identifying a series of interrelated landscape improvements modeled at a campus scale. We started the process by working with several UW-Madison partners to identify the best way to evaluate and improve primary water quality issues affecting the regional watershed. From here, our team of experts decided the best way to analyze the campus’s watershed impact was to develop a parametric model of all existing and proposed landscape conditions. This massive parametric model enabled our team to quickly measure the performance of several master plan iterations and test out alterations in footprints of roads, paths, buildings, parking facilities and landscapes. Each of our iterations were embedded with water quality data that would ultimately tell us if we were meeting or exceeding our regional water quality goals, while protecting historic and ecological sensitive landscapes that shape the everyday lives of students.

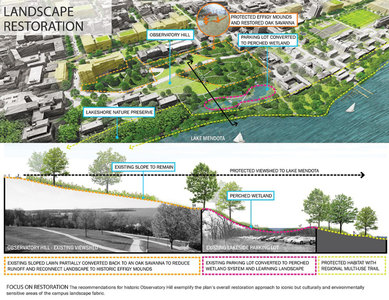

The resulting landscape master plan identifies both individual and multi-site based landscape recommendations that work as an integrated system to simultaneously improve water quality and campus identity. Take the historically significant campus effigy mounds, for example. The recommendations for the historic Observatory Hill exemplify our overall approach to iconic, yet culturally and environmentally sensitive areas of the campus landscape fabric. The plan not only reduces run-off through a restored oak savanna and converts an exhausted lakeside parking lot into a perched wetland, it also provides improved protection and interpretation for the Native American heritage of this key viewshed. The result is the enhancement of one of UW-Madison’s oldest landscapes—where future students, just as I used to do, will be able to enjoy sledding on cafeteria trays in below zero weather while taking in views of one of the most beloved lakeside settings in the nation.

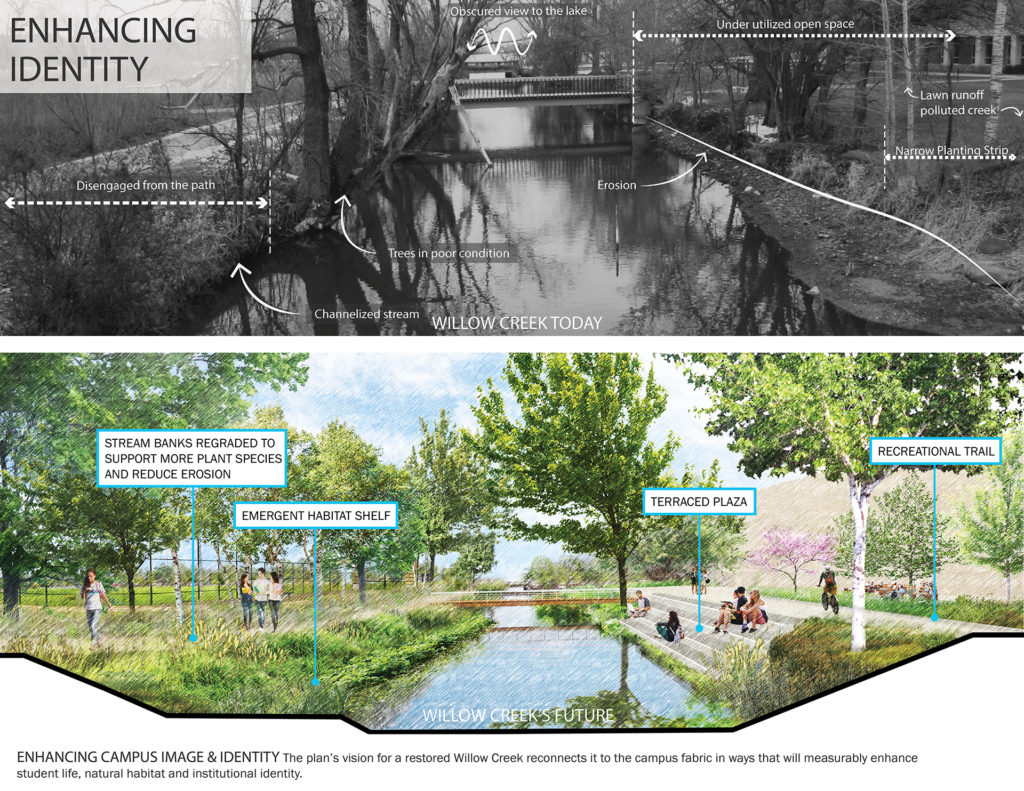

While our efforts placed considerable emphasis on the most iconic spaces, we also focused careful attention on landscapes that were not realizing their placemaking potential, such as the degraded Willow Creek corridor. As a student, I didn’t know the creek existed—the university had ignored Willow Creek for decades as development occurred around it. Now, in alignment with our approach, the updated plan’s vision for a restored Willow Creek will become the front door to a new type of campus district that is grounded in ecology and fully embraces students’ passion for more waterfront open space. With a reenergized campus setting, neither daydreaming students like me circa 2006, nor busy visitors, will be able to miss the future Willow Creek district.

In essence, this project highlights the pivotal role of the campus landscape—a physical campus facilitating the type of place-based learning and experience that cannot be achieved in isolation from its larger social and ecological context. Universities must now consider and promote a more progressive, comprehensive approach for integrating high-performance green infrastructure into an overall campus landscape master planning process in order to further enhance institutional culture and collaboration. Given the transformative future of high-performance campus landscape planning, it will be exciting to see how new benchmarks, standards and processes will continue to emerge and evolve as more universities begin to emulate the UW-Madison model.